For International Women’s Day 2020, I wanted to celebrate the work of one of my favourite artists. Magda Cordell may not be a household name, but you can find her arresting images of the female body displayed currently at Tate Britain.

At first glance, her large and colourful canvases appear to be modern re-interpretations of archetypal female forms, but closer examination suggest a series of meanings surrounding fertility, biological destiny, sexuality, and regeneration. Cordell’s figures combine engagement with post-war trauma, fear of nuclear annihilation and the explosion of contemporary mass culture to pose questions on the changing role and image of women in the mid-20th-century.

Working as an artist in post-war Britain, Magda Cordell was involved in the established of the Independent Group (IG). This movement, which embraced a new approach to cultural analysis, developing European modernism to intersect it with American popular culture and new advancements in technology, pioneered the basic principles of British Pop Art. Frustratingly, as a rare female voice amidst the “Fathers of Pop”, Cordell’s work has been little discussed and infrequently showcased in comparison to her male peers.

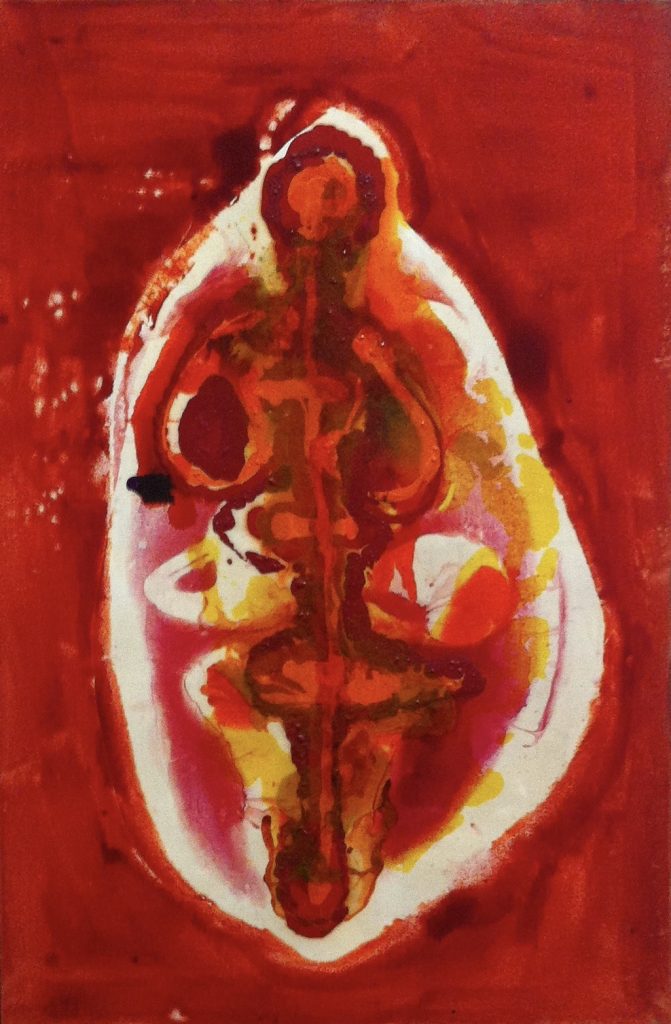

Tate, however, has two key works in their collection, from a series of numbered figures representing the female body: Figure (Woman) and No.12, which demonstrate the variety of ways she explored the primitively erotic and maternal body. Explosive chaos and tangled threads of paint vitalise her Figure (Woman) draw comparisons with styles of American Abstract Expressionism, while in No. 12a more calculated approach is taken to create a lurid glow of plastic paints. No.12, for me, demonstrates Cordell’s reimagining of womanhood most powerfully.

The form, which merges both a maternal and foetal shape, has a striking resemblance to the pre-historic figurine of the Venus of Lespugue, which frames Cordell’s work in the history of images of the procreative female body. However, her almost x-ray like vision of the gestating body under fluorescent lights place her canvas in dialogue with science fiction narratives of the 20thcentury, which had become a popular medium through which to challenge the cultural establishment. The unity of mother and child can be seen as a strong symbol of fertility, but for Cordell it is notan affirmation of biological destiny of woman. This form rejects both the popular images of female homemakers seen in 1950s advertising and the beauty standards reinforced by mass culture of the time. Instead, No.12 is a symbolic return to the womb, presenting a gynomorphic body in flux and most importantly at the moment of potentiality, that has the ability to adapt to new environments, and bring about new possibilities for the post-war era.

What is so exciting about reflecting on Cordell’s work on International Women’s Day is that it can be viewed through a 21st lens with re-enforced poignancy. In an era of #MeToo and climate school strikers where persistent anxieties question the direction of the human race, Cordell’s figures can still offer a hopeful vision: a “heroic femininity” and a female body which endures through time, trauma and multiple renewals.

Post by Olivia, British Tours

If you want to discover more about women artists or British post-war artists or would like a highlights tour of one of London's incredible galleries or museums, take a private tour with one of our expert guides